To the Nurses, I Am the Bed Whisperer!

Sep. 29th, 2022 07:42 pmUnfortunately, Not like that. But it’s still cool.

During my recent hospitalization, I was stranded on a hospital bed. Since I had fainted due to blood loss, I wasn’t allowed to get out of bed without an attendent. They even had frickin’s lasers watching and if the lasers sensed both feet on the floor an alarm would go off.

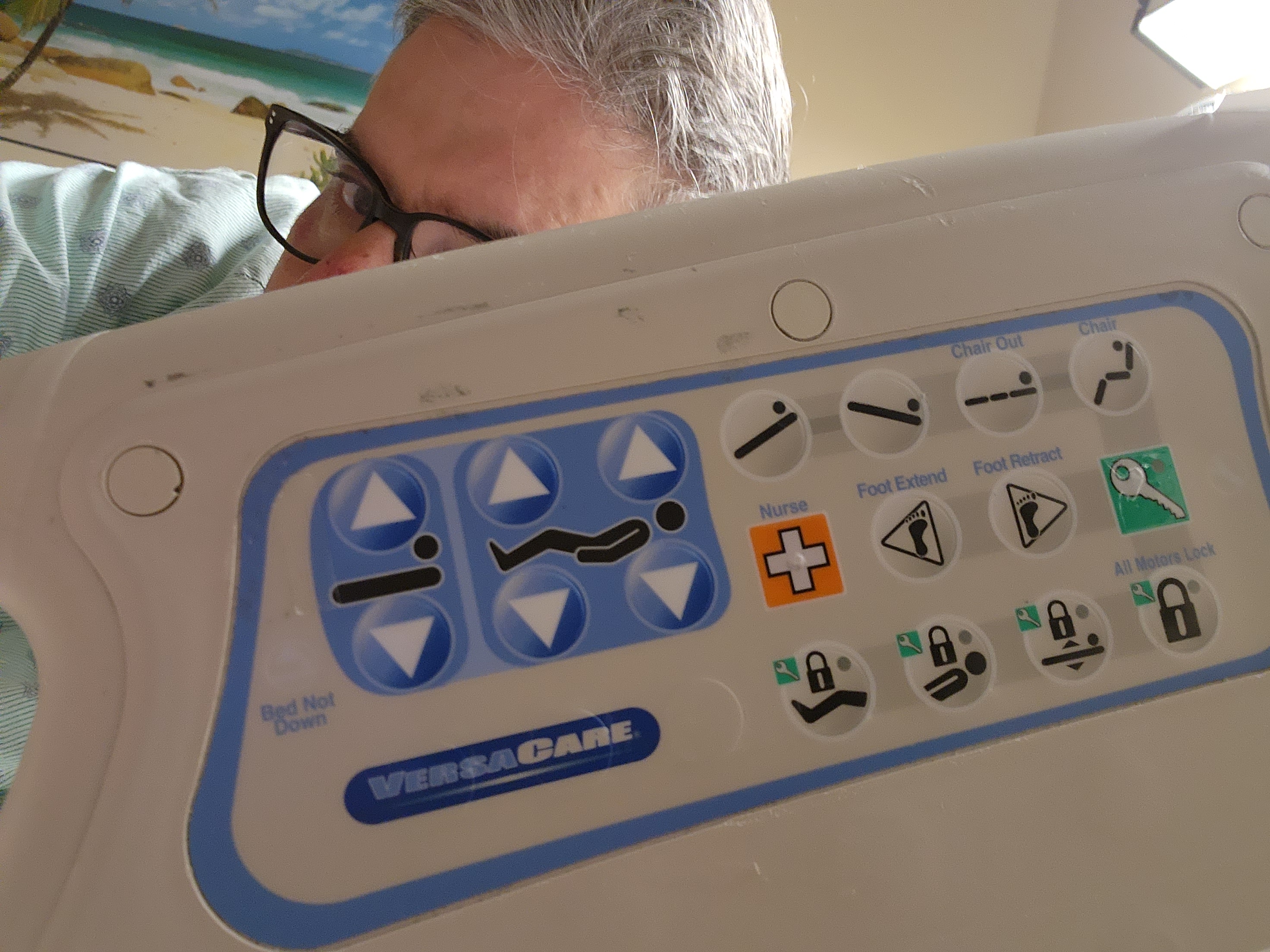

Nurse’s panel

Worse, the beds were broken. But, as someone else said recently, “I have ADHD, an internet connection, excellent research skills and poor self-regulation.” I took photos of the nurse’s side panel and underside to identify the make and model, downloaded the manual, discovered that it was no help at all, but ultimately found MedWrench, where nursing home technicians exchange gripes, complaints, and potential solutions. They hate this particular bed, but it’s popular because it’s cheap. Quelle surprise.

At one point, the nurse was struggling to make the bed go up. “Let me,” I said. “I’m the bed whisperer.” I reached through the handle, pressed the

Global Lock + All Lift Locks buttons simultaneously, then pressed the specific lift she was looking for (raising the head of the bed).“You are the bed whisperer! How did you do that?” She looked incredulous.

I explained, and I said I didn’t know how long that hack would last before the bed failed entirely. MedWrench says after that, you have to dig a panel open and re-seat a chip on the control board; it’s poorly held in and falls out if you move the bed too often. The most approved technique is to drill an 8mm hole at a location shown in various images and push the chip back in with a pencil eraser.

A little later, a nurse was checking on my roommate. She shuffled over to me and said, “Can you show me how to unlock the bed. The other nurse said you know how.”

“I can’t unlock it if that’s not working. But I can show you how to override the lock while you’re using the bed.” I showed her the trick (Hmm, two in the front, one in the back… I should nickname it The Shocker!), she went to the other patient, I heard the whirring and she shouted, “It worked! Thank you!”

Pretty much by the end of the day the nurses had all taught that trick to each other.

As I said, I have excellent research skills. But I refuse to believe that an entire hospital full of professional nurses had no one with curiosity and mediocre research skills to relieve a serious, ongoing problem. It boggles my mind that no one at that hospital had done what I’d done– downloaded the manual for a thing they use every day, then looked further when the instructions in the manual didn’t work!

A friend of mine suggested I have a programmer’s mindset– we get libraries and toolkits with crappy documentation and are used to supporting each other by giving out tips and tricks when we ask. But surely that’s not unique to my profession? Are we the last bastion of problem solvers in our species? No, I don’t believe that at all. But what to make of the fact that a patient had to solve one of their most commonplace irritations?