Last night, while meditating with my Muse headband, I encountered one of those Dark Behaviorist Patterns that are, to my thinking, one of the worst problems we have with apps and our networked world today.

The Muse Headband is gamified. I have no problem with gamification in general; I think it's an excellent documentation pattern, and done well is one of the best ways to get people to use your product effectively. But "done well" means done with the user's interests in mind; "done well" means executed with kindness and compassion for the user's time and patience.

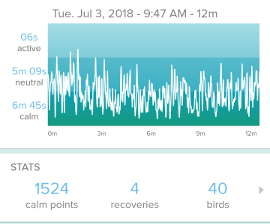

The gamification pattern for Muse is straightforward. While using it, it categorizes your brain state into one of four ranges: agitated, neutral, calm, and deep calm. There's a main score, and for that score it gives you 1 point for every second you're "neutral" and 3 points for every second you're "calm." It also has a score for how many times you transition out of "agitated," and another for how much time you spend in "deep calm," but that main score is the big deal. Depending on various scores, you get badges, like any gamified environment.

Since I usually meditate for 25 minutes (booking a half hour, with setup and teardown), my theoretical high score is 25⨯60⨯3 or 4500. Yesterday I hit 4400.

I got three familiar badges: "Marathon" (meditated for more than 20 minutes, which I get pretty much every day), "Lucidity," (calm for more than 20 minutes), "Birds of Eden" (persistent deep calm). I've gotten other badges, including the one labeled "Perfect Timing," which is awarded when you meditate for 10 minutes or more, but experience less than 60 seconds of "calm," and "Wanderlust," which happens when your mind starts to become agitated late in the session, indicating boredom and a lack of focus.

But I got one unfamiliar badge: "Precision Shooter." I looked up the description: "Your score was exactly 4400." I went and looked back in my history; I'd received this score once before, for a score of 2900. "Precision Shooter" is awarded when your score is evenly divisible by 100.

That's not just a terrible metric, it's a psychologically manipulative one. Nobody's going to train their brain for that kind of precision. It's not just a meaningless badge, it's one that's awarded out of sheer luck.

When psychology students do the rat behavior reinforcement experiment, they divide the rats into three groups: continuous reinforcement, fixed ratio reinforcement, and variable reinforcement. The first get a food pellet every time they press a button; the second get a food pellet every fifth press; the third set get a food pellet after a random number of presses. It could be two in a row, or it could take fifteen or more presses until the food comes out.

Then the researcher turn off the levers.

The first group of rats gives up pretty quickly. It worked, and now it doesn't. The second group gives up after a little while longer. The third group never gives up. Never. The behavior pattern lingers for months. The rats' brains have become addicted to the reward system itself and they'll keep slamming that lever even when they're not hungry.

"Precision Shooter" is a variable reinforcement mechanism. It only happens at random intervals because you meditate. It's meaningless in terms of one's progress (whatever "progress" means to Muse), but it is a form of manipulation meant to make you to come back and try again. And because it's tied to an observable metric, it feels like an "achievement," so the initial hook is powerful, even if that metric isn't one over which you can exert any actual control.

"Precision Shooter" is a Dark Behaviorist Pattern, and Muse should remove it from the product.

The Muse Headband is gamified. I have no problem with gamification in general; I think it's an excellent documentation pattern, and done well is one of the best ways to get people to use your product effectively. But "done well" means done with the user's interests in mind; "done well" means executed with kindness and compassion for the user's time and patience.

The gamification pattern for Muse is straightforward. While using it, it categorizes your brain state into one of four ranges: agitated, neutral, calm, and deep calm. There's a main score, and for that score it gives you 1 point for every second you're "neutral" and 3 points for every second you're "calm." It also has a score for how many times you transition out of "agitated," and another for how much time you spend in "deep calm," but that main score is the big deal. Depending on various scores, you get badges, like any gamified environment.

Since I usually meditate for 25 minutes (booking a half hour, with setup and teardown), my theoretical high score is 25⨯60⨯3 or 4500. Yesterday I hit 4400.

I got three familiar badges: "Marathon" (meditated for more than 20 minutes, which I get pretty much every day), "Lucidity," (calm for more than 20 minutes), "Birds of Eden" (persistent deep calm). I've gotten other badges, including the one labeled "Perfect Timing," which is awarded when you meditate for 10 minutes or more, but experience less than 60 seconds of "calm," and "Wanderlust," which happens when your mind starts to become agitated late in the session, indicating boredom and a lack of focus.

But I got one unfamiliar badge: "Precision Shooter." I looked up the description: "Your score was exactly 4400." I went and looked back in my history; I'd received this score once before, for a score of 2900. "Precision Shooter" is awarded when your score is evenly divisible by 100.

That's not just a terrible metric, it's a psychologically manipulative one. Nobody's going to train their brain for that kind of precision. It's not just a meaningless badge, it's one that's awarded out of sheer luck.

When psychology students do the rat behavior reinforcement experiment, they divide the rats into three groups: continuous reinforcement, fixed ratio reinforcement, and variable reinforcement. The first get a food pellet every time they press a button; the second get a food pellet every fifth press; the third set get a food pellet after a random number of presses. It could be two in a row, or it could take fifteen or more presses until the food comes out.

Then the researcher turn off the levers.

The first group of rats gives up pretty quickly. It worked, and now it doesn't. The second group gives up after a little while longer. The third group never gives up. Never. The behavior pattern lingers for months. The rats' brains have become addicted to the reward system itself and they'll keep slamming that lever even when they're not hungry.

"Precision Shooter" is a variable reinforcement mechanism. It only happens at random intervals because you meditate. It's meaningless in terms of one's progress (whatever "progress" means to Muse), but it is a form of manipulation meant to make you to come back and try again. And because it's tied to an observable metric, it feels like an "achievement," so the initial hook is powerful, even if that metric isn't one over which you can exert any actual control.

"Precision Shooter" is a Dark Behaviorist Pattern, and Muse should remove it from the product.